Im writing this both to help others and test myself so I will try to explain everything at a basic level. Any feedback is appreciated.

A Fenwick Tree (a.k.a. Binary Indexed Tree, or BIT) is a fairly common data structure. BITs are used to efficiently answer certain types of range queries, on ranges from a root to some distant node. They also allow quick updates on individual data points.

An example of a range query would be this: "What is the sum of the numbers indexed from [1,x]?"

An example of an update would be this: "Increase the number indexed by x by v."

A BIT can perform both of these operations in O(log N) time, and takes O(N) memory.

(least significant bit will be abbreviated to LSB and in this post means the bit with the first one in the binary representation. Length of an interval ending at index x is shown by len(x))

So how do BITs work?

BITs take advantage of the fact that ranges can be broken down into other ranges, and combined quickly. Adding the numbers 1 through 4 to the numbers 5 through 8 is the same as adding the numbers 1 through 8. Basically, if we can precalculate the range query for a certain subset of ranges, we can quickly combine them to answer any [1,x] range query.

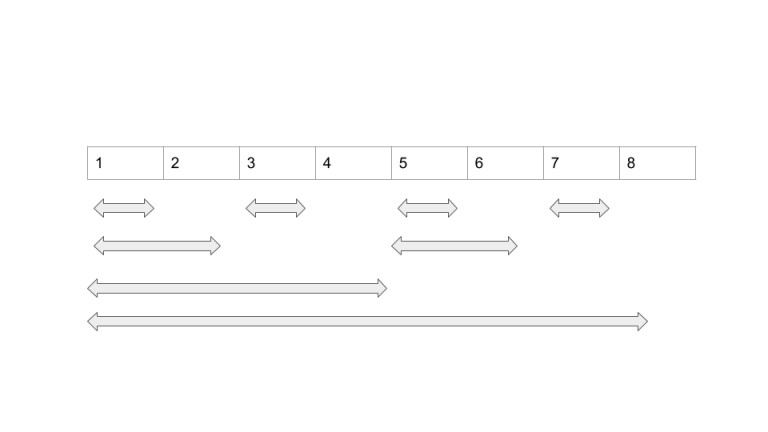

The binary number system helps us here. Every number N can be represented in log N digits in binary. We can use these digits to construct a tree like so:

The length of an interval that ends at index I is the same as the LSB of that number in binary. (We exclude zero as its binary representation doesn't have any ones.) For example, interval ending at 7 (111) has a length of one, 4 (100) has a length of four, six (110) has a length of 2.

This gives the tree some interesting properties which make log N querying and updating possible.

- Every index has exactly one interval ending there. This is obvious from the way we constructed the tree.

- Every range [1,x] is constructable from the intervals given, and every range decomposes into at most log N ranges. (This will be proved below)

- Every index is included in at most log N intervals. (This will also be proved below)

Proof that every range [1,x] is constructable from the intervals given.

A range query can be defined recursively [1,x] = [1,a-1] + [a,x] where [a,x] is the interval ending at x. x's which are powers of two are base cases as they contain the range [1,x] precalced. a is never below 1 as it is defined as the least sig bit in x, and x-LSB is either positive or a base case.

Proof that the range [1,x] can be broken down into a log N number of intervals.

let len(index) = length of the interval ending at index.

We use the above recursion [1,x] = [1,a-1] + [a,x]. as len(x) = LSB in x, and a-1 = x - len(x), the least significant bit in a-1 is greater than len(x) (unless x is a power of two, in which case it is only one interval). (Subtracting len(x) from x removes this bit.) Since len(a-1) > len(x), len(a-1) >= 2 * len(x). This means that we approach 1 at an exponential rate, so it takes log N intervals to construct [1,x].

(Note that visualizing x as a binary integer, and recognizing that at each step in the recursion the LSB is turned to zero, and that we end when x reaches 0, means that it takes n steps (where n is the number of bits) at most, and these n bits represent 2^n numbers, so we can reach the logarithmic number of intervals this way too.)

Proof that every index is included in at most log N intervals.

This is essential to proving that updating takes log N operations.

Looking at the pictures this seems true, lets proceed with a proof by contradiction.

Assume intervals ending at a and b with len(a)=len(b) intersect, and without loss of generality let b>a. If these intersect, that means b-len(b)<a. Note that - len(b) is just removing the least sig bit. As len(a) = len(b) both a and b are indentical from the least sig bit to their start. This also means that as b > a, the binary number above these digits for b is greater than a. Removing the least sig bit from b doesn't change b>a as, in binary, the greater number is determined by the leftmost digit, as every digit carries more weight than all the previous digits combined.

Basically: b = [B]10...00 and a=[A]10...00 with [B]>[A]. b-len(b) = [B]00...00 which is still greater than a, so b cannot intersect a.

As there are a log N number of interval lengths, and no two lengths of the same size intersect, this means that any index is covered by at most log N intervals. Thus, updating an index requires updates to at most log N intervals.

In the above proofs we have found the method for querying efficently, but we still don't know how to update the nodes.

How to update:

First note that as our ranges are defined by their rightmost endpoint, the range ending at x is the first range that contains x. So we need an algorithm that can quickly find the next largest range that contains x, and repeat until there are no more such ranges. The next range that contains x must be larger than the current one, so we know the next range's lsb > lsb of x. It turns out that the function next range = x + len(x) works. This is because this function increments the lsb to the next valid one.

Some people might notice a slight problem here, if we have a number like 111000, adding 1000 to that number gets 1000000, skipping a bunch of possible ranges. This is fine as the ranges that are skipped do not cover x. Trying to include the skipped ranges by removing ones just gets numbers that are lower than x, e.g. 110000<111000. Adding numbers to the end before increasing the lsb also doesn't work, as this moves the range ending further than the lsb increase does, e.g. 1110000 ends at 1100000 which is > 111000. The only way to increment to the next largest valid range is with x+=len(x).

Here is the procedure for updating a node x: update BIT[x], then add len(x) to x, repeat until x exceeds the size of the tree.

Now that we know our algorithms in theory, how do we implement them?

As every index only has one interval ending in it, it is possible to represent the BIT as an array. BIT[i] = the value of the interval ending at i.

Both update and query rely on getting len(x), or the lsb of x, easily. Thankfully, the bit operation (x&-x) returns the lsb.

Here's why:

let a=[A]10...00, then (thanks to 2-complements) -a = [A inverted]01...11 + 1 or [A inverted]10...00. Bitwise ANDing the two gets 000010...000, or the lsb of a.

Here is the actual implementation, using sum as the range query. (Note that we increment x so our tree is rooted at 1, as rooting at 0 causes problems.

int BIT[MAXN];void update(int x,int val) { ++x; while(x<=N) { BIT[x]+=val x+=(x&-x); } }

int query(int x) { ++x; int res=0; while(x>0) { res+=BIT[x]; x-=(x&-x); } return res; }

(I can't for the life of me figure out why the code isn't formatting properly... sorry.)(A little interesting fact is that x&=(x-1) functions the same as x-=(x&-x))

Thats it! Note that you can query for ranges [a,b] by performing query(b)-query(a-1). The same code can also be adapted to other range queries, but there are some pitfalls to look out for. Updating min and max doesn't always work, as you need to know the values in the range which you are updating, unlike in sum where all you need to know is the range's sum. For the same reasons you cannot query arbitary ranges [a,b] with the like you can with sums.

As a little aside, BITs are like a lightweight form of a segment tree. They take up less space (by a constant factor) and are quicker to code, but they are not as versatile as segment trees.

Again, this is my first time blog so any feedback is appreciated.

"The next range that contains x must be larger than the current one, so we know the next range's lsb > lsb of x."

Can someone explain why the next range must be larger than current one.

say x is [somenumber]1000. The any interval of size 1,2,4 doesn't cover x (as if we had such an interval a-len(a) >= x), we have already proven that nothing of the same size can intersect, therefore the only possible ranges are those who are larger. You can generalize this argument for other range sizes.

A fantastic video tutorial of Fenwick trees and how they can be useful is Algorithms Live Episode 0 by Matt Fontaine: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kPaJfAUwViY

Another good article for this concept. https://www.hackerearth.com/practice/notes/binary-indexed-tree-or-fenwick-tree/#c217533

This is really great!!

Please add some practice questions in increasing order of difficulty.

Can someone please give a proof of the update operation?

I don't think you need a proof by contradiction to prove that two intervals of the same length will not intersect. This is because if an interval has a length of $$$2^n$$$, then the number must be a multiple of $$$2^n$$$. And since all distinct multiples of $$$2^n$$$ must differ by $$$2^n$$$, the segments will never be long enough to touch each other.

Very nice prove for update!