Introduction

When it comes to "problem-solving techniques", there are roughly 3 levels:

- Concrete algorithms (Kruskal's algorithm, Li-Chao tree, fast Fourier transform)

- General patterns (dynamic programming, greedy, square-root decomposition)

- Meta-strategies ("how do I even go about solving this problem?")

There is some grey area, but in general this classification works well.

Many tutorials have been written about ideas that fall into 1 or 2. But very little has been written about the third category. On the catalog, I think the only blogs that really qualify are this and this. There is also this valuable comment. As to why there is so little written, I think I can identify two reasons.

- Most strong contestants don't really consciously think about these. After solving a problem with FFT, it's hard not to know you used FFT. If you used DP, even if you did it without thinking that it's DP, it's not hard to recognize that you used DP later anyway. But about things in the third category... it's hard to recall how exactly your thought process went. Furthermore, at least I have never really learned (i.e. read about and understood) anything from that category. Rather my thought process has developed from a lot of practice and experience.

- When writing about algorithms, it is easy to know you are right. You just prove it. But now we are veering into a more uncomfortable realm, where it is harder to understand what is correct or what is even useful. It is not as bad as writing about psychology, but still. Even with this blog, as I'm writing this, I think "does it even make sense?".

- It is not clear if writing blogs of this type actually helps anyone. I still maintain that in your ability to solve problems, the most important thing that you have control over is experience and seeking substitutes for that (algorithms to come up with algorithms, reading other people's thought processes) etc don't work. However there are many people who in theory should have a lot of experience but whose results don't reflect that.

It's far too much for me to write and describe exactly how my thought process works, and I'm not at all convinced that this would be useful for anyone. But I think I've identified something that beginners regularly get wrong, so I'll try my best to explain that. $$$~$$$

The idea

The forcing fallacy

Many beginners have developed this "technique" for solving problems. They look at the constraints or use some other, usually misguided, intuition to tell whether it is DP, greedy, or something else. They then try to "force" the chosen technique on it. With greedy it is usually easy, but will most likely lead to wrong solutions. With DP it is harder, but they still try.

Many times, after I've explained to someone how to solve some certain problem, they ask "but can it be solved with DP?". There are many reasons one might ask this, but I'm certain that in some cases, it is exactly this. Something in the problem made them believe that this problem must be solved by DP. They tried to solve it directly with DP, trying to figure out states and whatnot, and failed.

Similarly, there are many questions and blogs of the form "is this DP or greedy". For example, there was once a blog asking for help in a problem. One of the comments said "it must be DP because greedy is wrong". There are several things wrong with that statement.

- The obvious, simple greedy strategies you tried were wrong. Nothing is ruling out the possibility that there is a chain of interesting observations giving rise to a different, more involved greedy algorithm.

- Not greedy does not imply DP.

- This is simply the wrong question to ask at this point. "Deciding" whether to use DP or greedy and then forcing your choice is just a bad approach.

There are even more examples. There was a funny blog, where someone tried to feed cheaters wrong solutions, and the cheaters rejected these solutions, because they were sure the correct solution would be to use "monotonic stack". This gives a possible explanation: perhaps something in the problem made them think this problem is about this "monotonic stack" and they tried to force it.

This forcing fallacy also extends to more specific algorithms, not just more general patterns like DP. For example, I once saw some segment tree code that was just complete nonsense. And this is exactly what happened here. The problem was one with range queries — a beginner assumed that it must be solved with a segment tree and tried to force it instead of thinking about the nature of the queries in that particular problem. And it didn't work because the problem probably can't be solved using a segment tree and this beginner was trying to push a square peg into a round hole. What makes this more painful is that the solution to this particular problem was much simpler than a segment tree.

High-rated users can sometimes make it worse. A common phrase you hear after a contest is "oh, E is just dsu + stack" and like... no, it's not. You left out all the reasons about why it works, how to use them and so on. It is not possible to solve this problem by just knowing that it uses DSU and stack. It is, however very possible to solve it by knowing all the stuff you didn't tell me — I could probably come up with the DSU portion myself.

What to do instead of forcing

Maybe this technique of guessing and forcing DP or greedy works well enough for easy problems and got you to green, I can't really tell. Here's the thing though. Very few hard problems can be solved directly using greedy, DP or any common algorithm. They are used, yes, but you can't solve problems by simply deciding to use greedy.

In most problems, you are presented with some structure (broadly speaking). In a harder problem, you can't directly calculate the thing you are asked to. Instead, what you should do is try to understand this structure. I mean really understand it. Not understand the problem, understand what's going on inside. Gather observations. Maybe even forget for the moment what the problem is asking for and try to understand the situation in general. There will be examples below.

To conclude this section, think about it like this. You're solving an integral.

Do you look at it and decide that "this integral looks like I should do a some additions and multiplications"? That's what this is like. Yes, you do need to add and multiply, but that information does not help you in any way. The essence, the idea of the solution is somewhere else. The same is true in hard CP problems. You might do some greedy things and some DP, but knowing that in advance doesn't help you.

Nested Rubber Bands

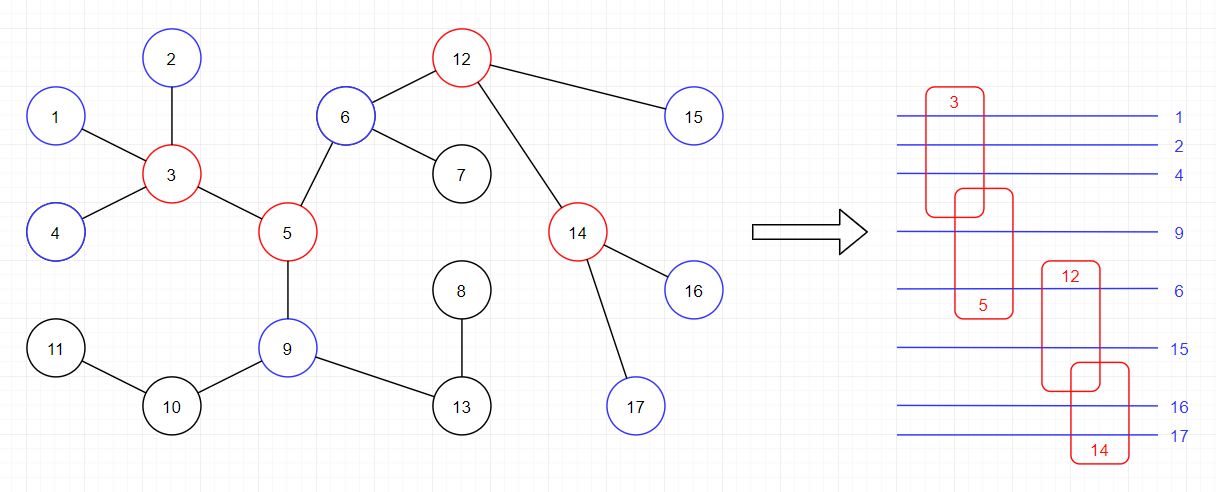

Problem. (1338D - Nested Rubber Bands) Given a tree. You want to draw the tree on the plane in the following way:

- Every vertex is represented by a closed, non-self-intersecting loop.

- Two vertices are adjacent if and only if their loops intersect.

What is the maximum length of a chain of loops in the drawing, where every loop is contained in the previous loop?

Why am I starting a blog (that's presumably for beginners) with a 2700 problem? Because it's a perfect example of what I'm talking about. In this problem, it's so blatantly obvious that you can't solve this problem directly by DP or greedy or some secret algorithm that only reds know about. In this problem, it's not even possible to create a naive solution for stress-testing. The topology-based problem statement stands in the way of everything you might try. There is no other way: you have to first understand what it really means to be able to put vertices in a chain like this. You must remove the geometry and topology, you need to find and prove some equivalent condition and you have to rephrase the problem into something that you can actually make an algorithm out of. Then you can do some DP (spoiler!) to solve the new and improved problem.

The new and improved problem. Given a tree. Pick two vertices and color some of the vertices in the path between them red. Then you may color some uncolored neighbors of the red vertices blue, in such a way that two adjacent vertices are never blue. What is the maximum number of blue vertices you can make?

Image stolen from the editorial

Yes, that problem is equivalent to the nested rubber bands problem! The new problem can be solved using DP. How to exactly come up with this transformation and how to use DP for the new problem are beyond the scope of this blog, but I think this perfectly illustrates the "two-phase" thought process.

- Gather observations, understand what's really going on, convert the problem into something you can make an algorithm out of.

- Solve the new and simpler problem directly, with DP, greedy or some classical algorithm.

Flipping Range

Problem. (1630D - Flipping Range) Given an array $$$a$$$ of length $$$n$$$ and a set $$$B$$$ of integers such that $$$b \le \lfloor \frac{n}{2} \rfloor$$$ for all $$$b \in B$$$. In one operation, you may pick a number $$$b \in B$$$ and change the sign of all numbers in a subarray of $$$a$$$ with length $$$b$$$. You may use this operation as many times as you like. What is the maximum sum of the array $$$a$$$ that you can end up with?

This is the perfect problem where misguided intuition will lead you to think about DP. Maximizing something with operations — that's DP, right? You try to formulate the states and... you're stuck. Because that's not what this problem is. Greedy may also seem enticing — go along the array and make the best flip at the time, right? Nope, that's wrong.

Forget the problem. Understand the situation.

Try to understand this. What are all possible subsets of positions that you can negate? Understand the space of all possible outcomes. Spoiler: once you understand them well enough, the solution to the problem will become trivial.

A nice thing to try is to solve a simpler variant of the problem. Often, a good idea is to think about the simplest non-trivial variant. Instead of having a set $$$B$$$ of operation lengths, let's just have one length, $$$b$$$.

Another good thing to always do is to cast out the irrelevant details. The irrelevant thing here are the values in the array. Right now, we are studying which subsets of the array one can negate. We do not currently care about the values other than that. So forget them, think about only "negated" vs "not negated". A binary choice. 1 for negated, 0 for not negated.

Now that we made these simplifications, let's start solving. The first thing we notice is that we can make the first $$$n - b + 1$$$ values whatever we want to. Simply go from left to right, if the $$$i$$$-th value is already what we want it to be, then leave it as it is. If not, we can negate the subarray starting at $$$i$$$.

But with this strategy, the last $$$b - 1$$$ bits are out of our control. It seems we can't do anything about them without messing up the first $$$n - b + 1$$$ bits. Yet there also seems to be some regularity as to what happens to the last $$$b - 1$$$ bits. I recommend you try this on paper. I'll take $$$n = 11$$$ and $$$b = 5$$$.

Notice anything? There seems to be a cyclic pattern. If we try to set just one bit to 1 on the left, another 1 pops up on the right, or once every 5 times, all the bits on the right are set to 1. Can we understand this better? And can we be sure that it is not possible to end up with a different configuration on the right if we apply the operations in a different way?

A good thing to think about in problems like this are invariants. Invariants are things that don't change after you perform an operation. In this case, look at only the positions that are divisible by $$$b$$$. Exactly one bit changes there. Now look at only the positions that give 1 modulo $$$b$$$. Exactly one bit changes there too. And so on.

Let's divide the positions into buckets by their indices modulo $$$b$$$. Every time we do an operation, the number of 1-s in each bucket changes exactly by 1. At any time, the numbers of 1-s in buckets must either be all odd or all even. And that is precisely what we needed! This explains the phenomenon we saw earlier. We can make the first $$$n - b + 1$$$ elements into whatever we want, and the last $$$b - 1$$$ positions are precisely what we need to "correct" the parities. There is one bucket we can't change with the last $$$b - 1$$$ positions, and the rest are needed to change every other bucket into the parity of that bucket.

Now back to the original problem, but still with just one $$$b$$$ rather than a set $$$B$$$. We must choose "odd" or "even", and then choose from each bucket an odd (even) number of elements to negate. Suddenly, the problem is easy! In each bucket you can sort the elements and figure out the prefix to negate if we have to choose an odd (even) number of elements.

In a loose sense, this is greedy. It is nothing like the simple, obvious greedy we talked about at the beginning. It's not possible to find this greedy unless you go through a thought process similar to above, even if you cut a few corners here and there. The person saying "it's not greedy, therefore it is DP" would never have reached here.

I'll not delve into the solution with a set $$$B$$$ instead of just one width $$$b$$$, but it is not hard and not the crux of the problem.

By the way, this is a very common technique in problems like "you are given operations X and Y, can you make $$$t$$$ starting from $$$s$$$/what is the lexicographically smallest $$$t$$$ you can make from $$$s$$$/how many different $$$t$$$ can you make from $$$s$$$".

- You identify some invariant, something that doesn't change when you apply the operation.

- You prove, using some construction, that anything satisfying this invariant is actually reachable.

Some people think these problems are more creative and interesting than, say, data structure or string problems, but they have their own standard tricks and techniques just like everything else.

What does it all mean?

In all problems I have shown, there are essentially two parts to the solution.

- Deeply understanding the problem, familiarizing yourself with the situation, making observations, reductions, rephrasing the problem.

- Actual computation, often in a relatively standard way, possibly a greedy algorithm or DP.

Of course, this picture is simplified. In practice, the steps are very much intertwined, and it is usually hard to write down the two phases so explicitly separately. But the general idea stays the same. Doing greedy or DP happens at the end of your thought process, not at the beginning of it.

Finally, I must say that I myself am guilty of trying to force an algorithm (namely, FFT) on problems and learned pretty quickly that it doesn't work. This is in fact the source of the name -is-this-fft-.